Researchers from the Shenyang National Laboratory for Materials Science, the Institute of Metal Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IMR, CAS), have achieved a major breakthrough in the study of metallic bonds by successfully stretching a chain of gold atoms to a record 46% strain. This work provides unprecedented experimental insights into how the fundamental bonds in metals behave under extreme deformation and how this affects their electrical properties.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, investigated gold atomic chains—the ultimate one-dimensional structures where atoms are linked in a single row. Using an aberration-corrected high-resolution transmission electron microscope, the team meticulously stretched these atomically thin wires while simultaneously observing their structural changes with atomic precision, all while ensuring a clean, contamination-free environment.

The findings reveal dramatic and non-linear behavior. While the bond lengths stretched uniformly at low strains, exceeding 12% strain triggered a remarkable shift. The bonds no longer elongated together; instead, they exhibited a "discrete" or step-like stretching pattern, characterized by alternating short and long bonds—a configuration known as dimerization. This is the first direct experimental observation of such behavior in a pure metal system at such high strains.

Most strikingly, this extreme structural transformation had a profound impact on electrical conductance. As the strain increased, the flow of electrons through the atomic chain underwent a stepwise transition: it dropped from the well-known integer quantum conductance values to fractional quantum values, and eventually, under the highest strains, the chain became insulating. This direct correlation between specific atomic configurations (bond lengths) and distinct quantum conductance states establishes a new principle for controlling electrical properties at the atomic scale.

The discovery of this strain-controlled quantum conductance switching mechanism opens new avenues for designing next-generation electronic devices. It provides a foundational concept for developing ultra-miniaturized components like atomic-scale switches, memory elements (memristors), and quantum point contacts, potentially driving innovation in fields ranging from high-density data storage to quantum computing.

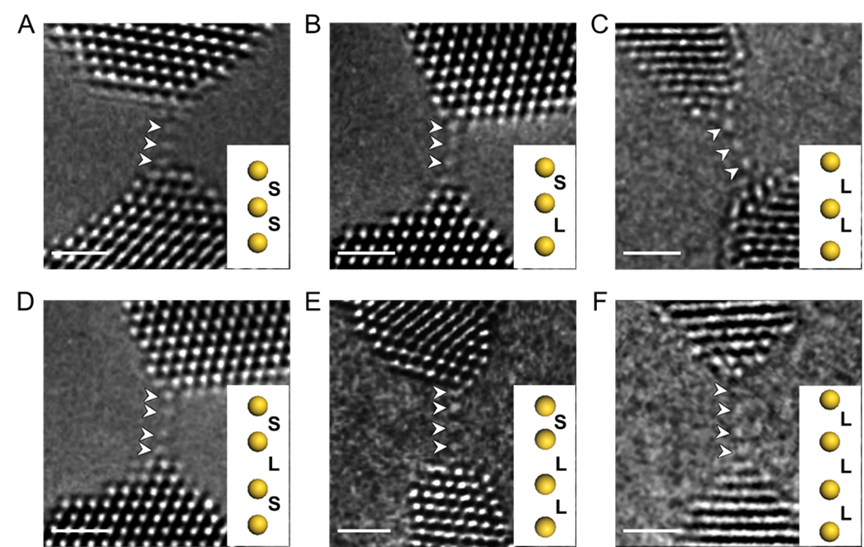

Aberration-corrected high-resolution transmission electron microscopy images of atomic chains with different configurations. (Image by IMR)

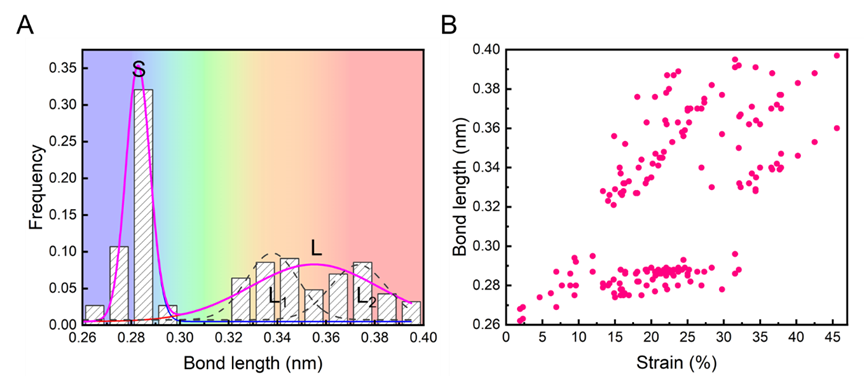

Bond length distribution in gold atomic chains. The bond lengths exhibit a discrete distribution, concentrated in two distinct ranges: 0.260–0.296 nm (short bond S) and 0.321–0.397 nm (long bond L). (Image by IMR)

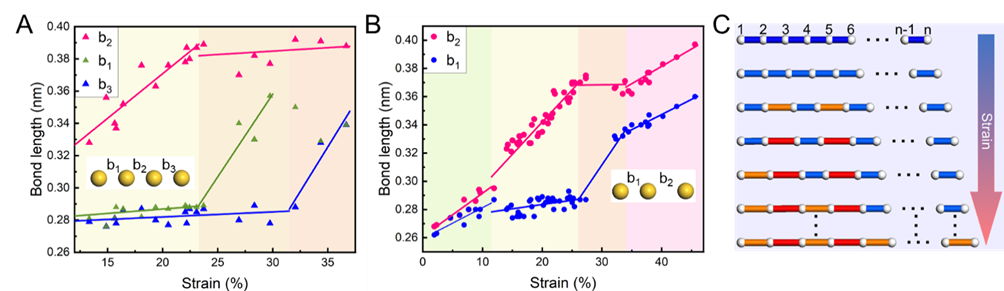

Variation of bond lengths along the atomic chain with increasing strain. At low strain stages, all bond lengths elongate linearly and uniformly. When strain exceeds 12%, some bonds preferentially transition from the S-state to the L-state, while the remaining bonds temporarily remain in the S-state. Finally, with further strain increase, the remaining S-state bonds sequentially transition to the L-state. (Image by IMR)

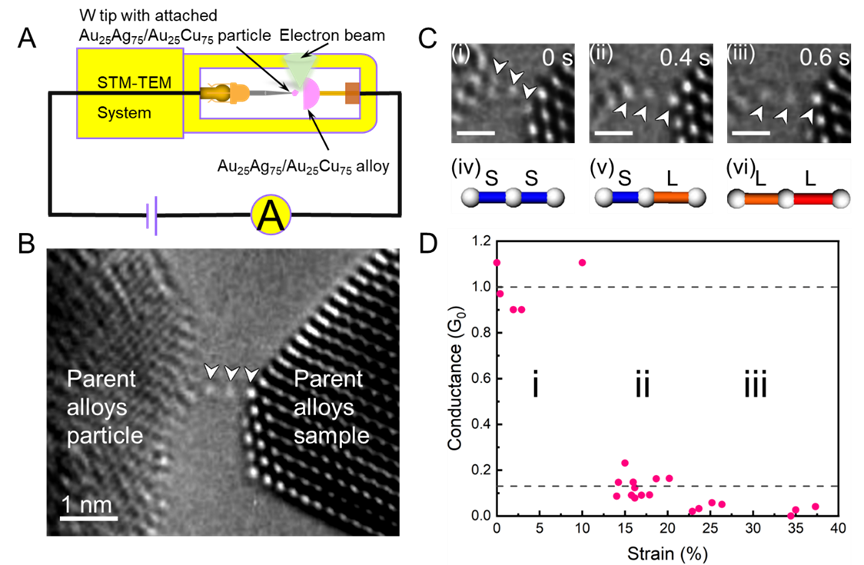

In situ observation and measurement of structural and conductance changes in a gold atomic chain. As strain increases and the atomic chain evolves from the S–S configuration through the S–L configuration to the L–L configuration, its conductance decreases stepwise, corresponding successively to the integer quantum level of 1G₀ (where G₀ = 2e²/h is the fundamental unit of quantum conductance), a fractional quantum state of 0.13G₀, and finally approaching zero to become an insulating state. (Image by IMR)